Interview with Peter Jenkins, Boston Warehouse

Hello! Today I have an especially worthwhile post: I was able to interview Peter Jenkins, Founder and CEO of the Boston Warehouse Trading Company — the company that designed, made and sold more spreader sets than any other company, and which was almost certainly the company that originated the entire concept of resin-handle cheese spreaders.

I was eager to speak with Mr. Jenkins to find out how Boston Warehouse started making spreader sets, and what their process for designing and producing them involved. He very obligingly answered my questions.

A little background: Peter Jenkins, a native of England, founded his company in 1974 to import giftware and kitchenware from European manufacturers, like ceramic items from Italy. (One of the company’s best-selling items during the 1980s was an unglazed ceramic garlic baker.) That’s why the company is located in Boston — because in dealing with Europe, that was a convenient and direct place for a headquarters and warehouses. Although by the 1990s, like most import companies, BW was moving most of its manufacturing to Asia, as Taiwanese and Chinese manufacturing grew in capability.

When I asked him just how BW got into the business of making resin-handle spreader sets, he recalled that he had originally been approached by a sales representative, perhaps from Minneapolis, who suggested that ceramic-handle spreader sets might be the sort of product that would do well for his company. He considered the idea, but some time later, perhaps at a trade show in China or Taiwan, he met representatives from a factory that made spreader sets with resin handles.

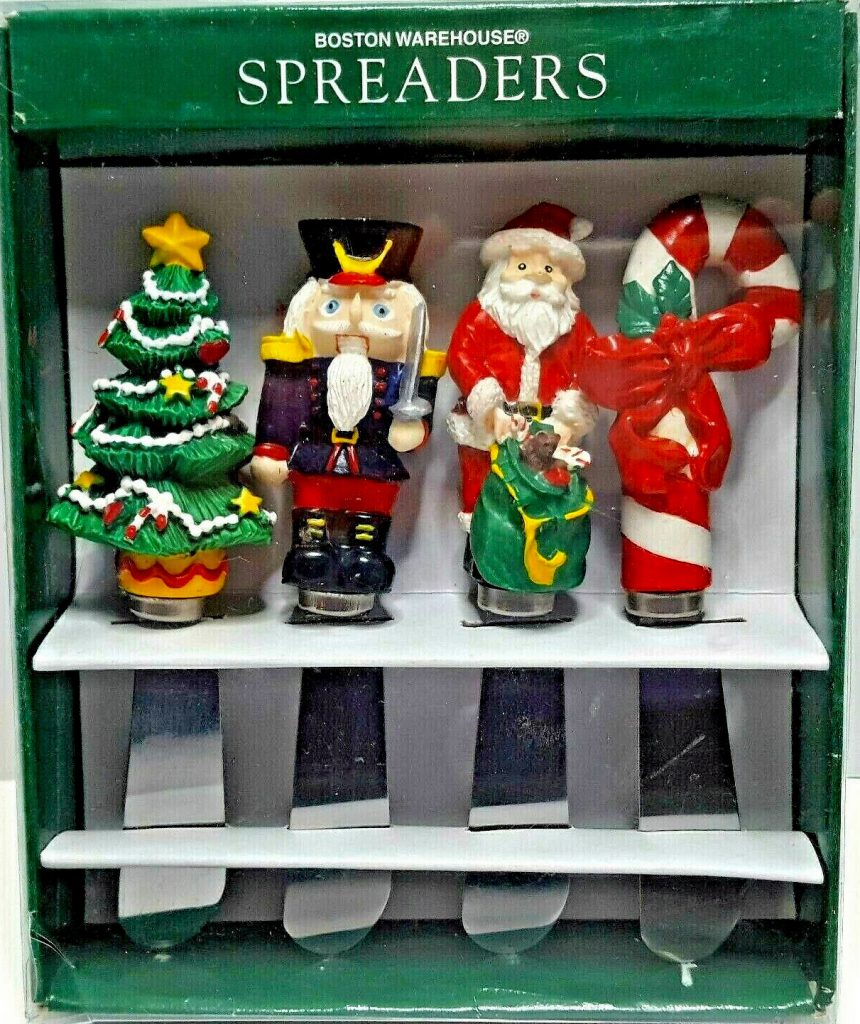

The polyresin material, together with hand painting, allowed for a much finer detail of design than ceramic material with a ceramic glaze. Intrigued by the idea, he directed graphic designers at his company to come up with half a dozen designs for sets of four spreaders. He was not certain off the top of his head which designs were the first to be made — except for the set of Vegetable Spreaders (12-102), which he remembers with certainty. But I have seen six sets with 1993 copyright dates on the back of the cases: Those Vegetables, Garlic (12-106), Fruits (12-107), Corn (12-138), Nutcracker (12-114) and Bar Condiment (12-190, of which I have no image yet, only an image of the back of the case).

Those first sets must have sold fairly well, because within a couple of years, the company was designing at least two dozen new sets each year — and more than 60 different sets in 1999 alone!

Mr. Jenkins confirmed my theory: to his knowledge, Boston Warehouse was the first American company to sell spreader sets here in the United States. He believes that other companies such as Cardinal/Spreadables started making and selling spreader sets following Boston Warehouse’s success.

All of Boston Warehouse’s sets were designed by BW graphic designers, either from their own designs, or based on the artwork of various American artists such as Guy Buffett, Debbie Mumm, Susan Winget and other artists to whom the company paid licensing fees (those artists approved the designs made by BW graphic designers).

The designs were drawn on paper by the graphic designers, and because they were designing 3D sculptures on 2D paper, the drawings were done from several different aspects, to show all the sides and a top view. After the designs were approved by the company directors, they were mailed to the factories in China (BW always tried to have two to three different factories making their products, so as not to become too dependent on any one in case of disruptions). There at the factory, prototype models were made to the designs and mailed back to the company for modifications or approval. Once approved, the prototypes were used to create molds from which the sets were cast.

Production runs for each design of four spreaders were, at minimum, 2,400 sets per run (and often much larger production runs). So even the sets that hardly ever appear on Ebay were made in runs of at least 2,400 sets.

Some of the most popular designs, the Breakfast Spreaders (12-137, 1995), which Mr. Jenkins believes was the all-time most popular set BW ever issued, and Christmas Spreaders (12-108, 1994), etc., were issued multiple times, under the same and different model numbers.

Boston Warehouse also made spreader sets for private label companies to label under their own brand names, such as Williams-Sonoma and Harry & David.

And Mr. Jenkins also cleared up another question for me, about the different cardboard case designs for spreader sets. Most of the early sets were sold in plain dark green cardboard cases; by around 2000, the cases became more brightly colored and were printed with colorful graphics as well. But many of the cases seen on Ebay are plain, brown unfinished cardboard (these mostly have dates of 1998 and 1999).

I wondered if the plain brown cases were for reissued sets, or for sets sold to discount retailers such as TJ Maxx. But Mr. Jenkins asserted that the brown cardboard cases were simply another marketing “look” for the spreader sets, as natural cardboard was a popular style.

Mr. Jenkins told me that BW sold one million spreader sets a year during the peak years of their popularity (likely the years around the turn of the millennium).

They were a tremendously popular product, one that almost universally delighted the product purchasers for retail stores (Boston Warehouse is a wholesale company that sells mostly through retail stores, not directly to consumers, so it was the product purchasers for those stores that BW salesmen had to impress). This widespread appeal is why Boston Warehouse designed nearly 1,000 different sets over a period of more than 20 years.

Boston Warehouse deserves to be recognized for originating the concept, and for the extraordinarily wide variety and wonderfully clever designs of their spreader sets — sets that delighted millions of customers for many years. And although currently the popularity of resin-handle sets has faded for retail stores, collectors still deem them worth collecting and are perhaps even more delighted when finding secondhand sets than their original purchasers were.

Many thanks to Peter Jenkins for speaking to me, so that I can document Boston Warehouse’s important originating role for the whole concept of spreader sets. And also much appreciation to Diane Taubner, Executive Vice President of Sales for Boston Warehouse, who put me in touch with Mr. Jenkins, and who also took the time to generate a list of the numerous spreader set models that the company has made, making my Boston Warehouse Spreader Database far more accurate and useful. Many thanks again!