All About Cheese Spreaders

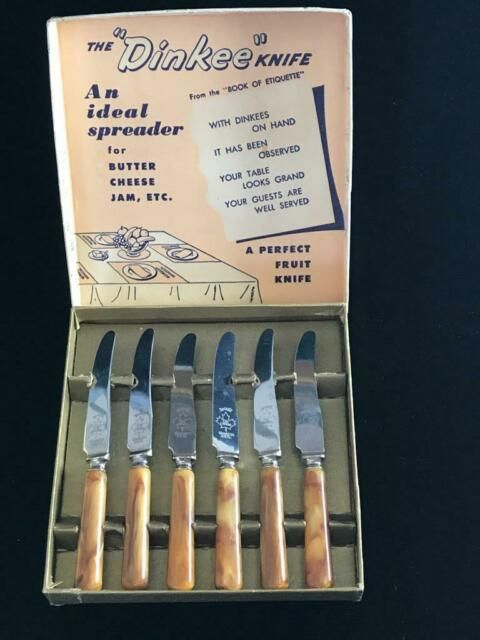

The term “cheese spreaders” as used by Americans describes short-bladed, short-handled knives (usually less than six inches in length) with rounded blades, used primarily for spreading soft cheeses on crackers or bread. They are also sometimes called “butter spreaders” or sometimes for fancy brands, “pâté knives.”

The handles of spreaders can be made of many different kinds of materials (including metals, woods, ceramics, plastics, and other materials such as real geode rocks and bamboo).

But, actual materials aside, there are three main types of handles on cheese spreaders:

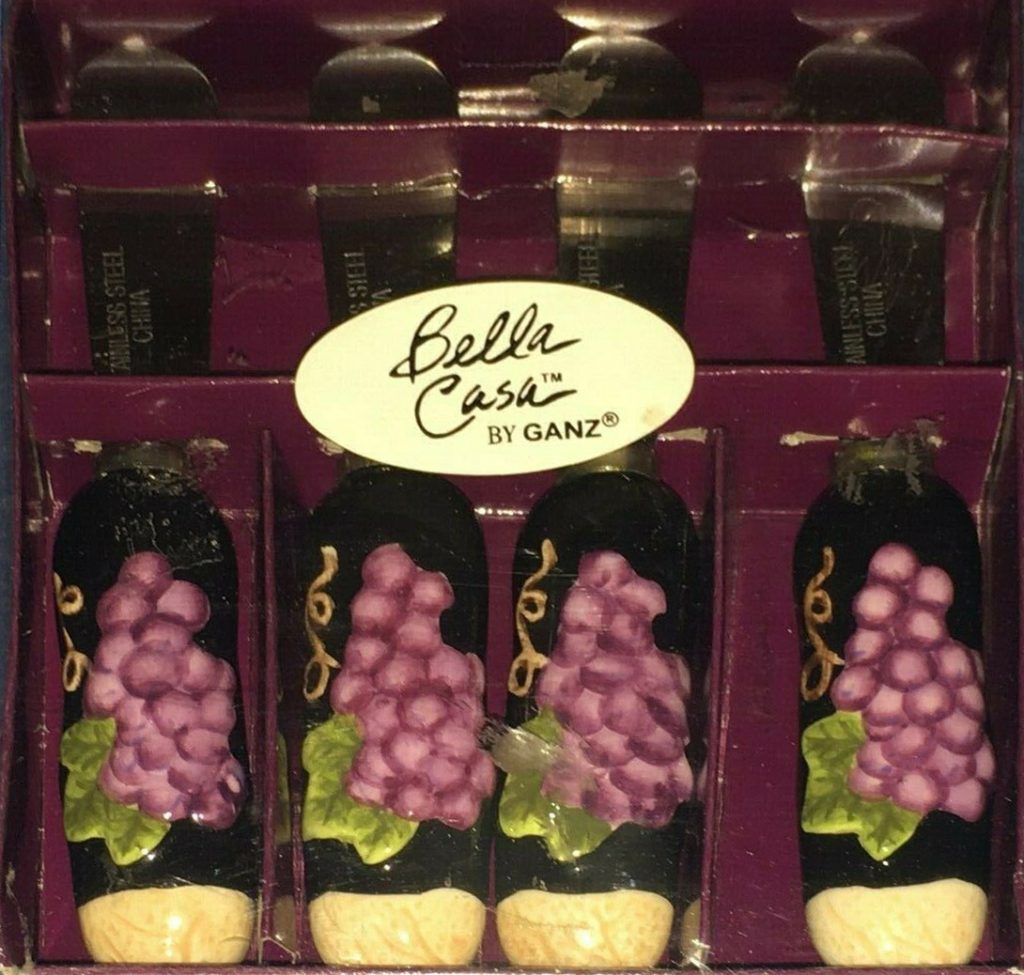

- Functional/Decorative Handles: Traditionally the handles of cheese spreaders were made of metal (including ornate gold and silver designs), followed by ceramic handles, and later on, plastics. The handles are chiefly functional and often decorative as well, either through the beauty of their materials, or through the patterns inscribed or molded into their handles.

Not unattractive, but mostly functional.

- Pictorial Handles: These are largely flat handles on which a design or picture is painted. They can be made of molded resin, the more traditional porcelain, or other materials. There are also spreaders with only words painted on them (usually clever sayings of some sort). The key is that these are largely two-dimensional depictions that indicate a theme or idea on the handles.

- Figural Handles: The spreaders that I collect, and which are the main subject of this blog, have handles that are molded into three-dimensional objects and painted to look like recognizable things, such as people, animals, foods, etc. These are mostly made of molded resin (although I do also have a few with molded metal or ceramic handles). Most resin handles are hand painted.

A History of Spreader Knives

Spreader knives came long after sharp knives, which are one of the earliest tools invented by humans. By at least the medieval period sharp knives were being carried in sheathes by people for eating at table (as well as for numerous other purposes). According to Wikipedia, sharp pointed knives were banned at dinner tables by French King Louis XIV in 1669, to prevent deadly violence after too many cups of wine. Whether due to this edict or not, special dinner knives with dulled blades began to be used in combination with forks and spoons during the 1700s.

The invention of Sheffield Plate (a thin layer of silver sandwiching a middle layer of less-expensive copper) in England in 1743 allowed the growing middle classes of 19th century England, Europe and America to purchase silverware for daily use. The invention of stainless steel in 1913 made flatware even more affordable, and it is still the standard material used for cutlery and flatware today.

Silverware for specialized uses, such as fish knives and cocktail forks, were developed and refined during the 19th century, and butter knives, shorter versions of the usual dulled dinner knives, came into use during this time. There were two kinds of butter knives: First, the master butter knife (used for cutting slices of butter out of the communal butter dish, which it accompanied) has a point used for spearing the pat of butter, and often a notch at the top to differentiate the cutting edge of the blade from the non-cutting edge. The second kind of butter knife, individual butter knives or butter spreaders, were set at each individual place setting and were used by each person to spread butter on their own food.

(Wikipedia)

in molds like later plastics and resins). They were made by a Canadian company, likely in the early 1950s (Bakelite was rarely used after the 1950s).

Japanese Ceramic Figural Spreaders

By the 1980s, Japanese manufacturers had begun to make the first spreader knives with figural porcelain handles and stainless steel blades. I suspect that the Japanese originated the idea of figural spreader handles, ones that depicted various objects.

If true, this would not be entirely surprising, as the postwar Japanese ceramic industry turned out hundreds of thousands of glazed figurines and tableware such as salt & pepper sets in the shapes of animals and people for export (now referred to as Occupied Japan collectibles). Plus, the Japanese seem to have a fascination with cuteness or kawaii in Japanese, personified by Hello Kitty and those lucky cat figurines with one paw raised for good luck. It’s not a big leap from ceramic figurines to cute little knives with miniature ceramic fruits for handles.

Resin Figural Handle Spreaders:

Most spreaders with figural handles are now made of polyresin, which can be cast in much more finely detailed shapes (it’s what military models are made of), and can also be painted with far more detail than ceramic glazes.

Spreaders are nearly all made in factories located in China (most blades are inscribed with some version of “Stainless China”). In fact, the rise in the popularity of figural resin-handled cheese spreaders coincides with the rise of Chinese manufacturing following China’s economic reforms begun in 1979. By 1990, China’s manufacturing sector had grown to encompass the bulk of such labor-intensive manufacturing for resin figurines and other items — like polyresin spreader handles.

Polyresin manufacturing is indeed labor-intensive, with the following steps (and click here for an article with pictures of the process at a Chinese factory: https://www.theodmgroup.com/manufacturing-polyresin-figurines/):

- First, the handles are designed, often by graphic designers in the US companies for whom the products are manufactured.

- The designs are sent to the factory, where factory managers figure out the specifications for manufacturing them.

- Originals are made by hand and approved, and two-sided molds are cast by hand from clay or rubber using those originals.

- The molds are used to manufacture as many handles as are needed, by hand-pouring liquid resin and a curing agent into the molds and heating them, causing the cast shapes to harden.

- The handle shapes are removed by hand from the molds and sanded to remove seam marks made where the two halves of the mold met.

- Handles are then painstakingly hand painted in batches by workers using tiny brushes and acrylic or enamel paint.

- The stainless steel knife blades are inserted into the handles and the spreaders are inspected, before being packaged by hand (often putting four different designs of handles per set in each case), in custom clear-lid cardboard cases printed with company information and marketing images for resale.

- The packed cases are boxed up and the boxes are stacked on pallets and sent by truck to a Chinese shipping port, where they are packed into a shipping container and loaded onto cargo ships. They are unloaded at the port of entry where customs duties are paid and then shipped overland to the company that ordered them, which then distributes them for retail sale.

All of this involves a great deal of hand labor, with very little factory automation — which is why cheese spreaders often don’t look exactly identical, especially the paint.

Here’s a short video showing the manufacturing process at a Chinese factory for polyresin figurines, which is very similar to that for spreader handles (except on a larger scale per unit cast):

So keep in mind just how much labor has gone into these little items, the next time you hold a set of cheese spreaders in your hands!

But who, you might wonder, engages and pays for the Chinese factories to make all these cheese spreader sets in the first place?

Boston Warehouse

Polyresin figural spreader handles were probably first widely manufactured for Boston Warehouse, a company established in 1974 by British ex-pat Peter Jenkins. His company started out importing European kitchen and housewares items; the company’s most popular items in the 1980s were a ceramic garlic keeper and a ceramic garlic baking container.

It was probably to accompany the garlic baker that Boston Warehouse came out with this set of spreaders in the early 1990s, perhaps to spread the soft roasted garlic paste on bread:

At least five other spreader sets were issued by Boston Warehouse in 1993: sets of vegetables, fruits, corn, bar condiments and Christmas nutcrackers. By this time, Boston Warehouse had switched from importing most of its items from Europe to having them made in Taiwan (the 1993 spreaders have Stainless Taiwan stamped on the blades). But perhaps within a year, it moved to manufacturing in mainland China, like many import companies were doing at that time (at least some spreaders with 1994 copyright dates are stamped Stainless China).

By the late 1990s, resin-handled spreaders were a hot new thing, and Boston Warehouse was making numerous new designs each year. In 1999 alone they came out with at least 70 new sets of four spreaders, and the company partnered with a series of mostly American artists to design new sets, including Debbie Mumm, Susan Winget, Warren Kimble, Jilly Walsh, Anna Maria Horner, Dan Morris and Guy Buffett, and the pajama company Nick & Nora.

Boston Warehouse couldn’t keep this trend to themselves, and other companies caught on during the ’90s and early 2000s, including:

- Cardinal Spreadables

- Centrum

- Ambiance Collections

- Out of the Woods of Oregon

- Supreme Housewares

- Mr. Spreader

- Retailers such as Williams-Sonoma, Target, TJ Maxx and Kohl’s often had sets made for their stores

- Companies such as Christmas ornament-maker Christopher Radko and gift basket company Harry & David had their own small lines of spreaders

- There were a few spreaders made for licensed products such as Disney characters, McDonalds, Pillsbury Foods, Grey Poupon, Heinz, etc.

Figural spreaders depict numerous different subjects: people, animals, foods; and objects or designs relating to holidays (there are more Christmas spreaders than any other subject), sports and other topics.

Dip Bowl and Spreader Sets: Some spreaders are sold as part of a set of bowl & matching spreader. To me, these are less interesting because they usually only have one spreader but take up a lot more room to store (leaving less room for spreaders themselves).

Themed Spreader House and Spreaders Sets: There are also “spreader house” sets: a base “house” in which to store and display accompanying spreaders. (It’s referred to as a “spreader house” even if the display base does not actually depict a house — a picnic table holding picnic food spreaders, or a large spherical orange holding orange slice spreaders are both referred to as “houses” in which to house the accompanying spreaders:

Boston Warehouse made nearly 60 spreader houses; Cardinal, Centrum and Ambiance Collections were also primary manufacturers of these. I have to admit a certain fondness for spreader house sets, despite the extra storage room they take — they are designed around the spreaders, and the relation between the house and the spreaders is sometimes quite clever and endearing.

The End of an Era

The “golden age” of figural spreaders lasted from the mid-1990s until around 2010. Resin-handled cheese spreaders declined in popularity among the general public starting around 2005, and by 2010 the trend was largely over, with far fewer new designs offered each year. Boston Warehouse does not make any new designs these days, and only a few companies still sell new ones online now.

Most spreaders sold today are more ornamental in design, or only loosely figural, either ceramic ones with modern designs, or fancy silver or gold-tone handles. The new spreaders are often beautiful objects, but they lack the attention to detail and clever humor of the best of the resin-handled spreader sets.

A Future Reappraisal?

But spreaders from the “golden age” are still available online at Ebay, Etsy, Poshmark and Mercari, and the variety and number of them can be astounding.

Read on to understand why I think spreaders are worth collecting: Next>>>